A couple of months ago I have written about some coastal ‘chevron dunes’ that have been interpreted as the onshore deposits of humongous tsunamis. The subject has been on the tip of my fingers for quite some time and I thought I managed to google up most of the related papers, news articles, and blog posts, but it turns out that I missed one highly relevant discussion: in the January 2008 issue of GSA Today, there is a short paper by Nicholas Pinter and Scott E. Ishman of Southern Illinois University, entitled “Impacts, mega-tsunami, and other extraordinary claims“. [Note to self: looking things up in Google and Google Scholar is not always enough, not even for blogging.]

A couple of months ago I have written about some coastal ‘chevron dunes’ that have been interpreted as the onshore deposits of humongous tsunamis. The subject has been on the tip of my fingers for quite some time and I thought I managed to google up most of the related papers, news articles, and blog posts, but it turns out that I missed one highly relevant discussion: in the January 2008 issue of GSA Today, there is a short paper by Nicholas Pinter and Scott E. Ishman of Southern Illinois University, entitled “Impacts, mega-tsunami, and other extraordinary claims“. [Note to self: looking things up in Google and Google Scholar is not always enough, not even for blogging.]

Pinter and Ishman criticize both the idea that several impact-related megatsunamis occurred during the last 10,000 years and the hypothesis that a 12,900 year old impact caused “Younger Dryas climate event, extinction of Pleistocene mega-fauna, demise of the Clovis culture, the dawn of agriculture, and other events”. The first idea is promoted by Dallas Abbott (at Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory) and her co-workers, but there is no real peer-reviewed publication yet; the second has been put forward by Richard Firestone (of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) et al. in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and a book. The evidence for the 12.9-ka impact includes magnetic grains, microspherules, iridium, glass-like carbon, carbonaceous deposits draped over mammoth bones, fullerenes enriched in 3He, and micron-scale “nanodiamonds”. Pinter and Ishman suggest that

the data are not consistent with the 4–5-km-diameter impactor that has been proposed, but rather with the constant and certainly noncatastrophic rain of sand-sized micrometeorites into Earth’s atmosphere.

But I am going to focus here on the ‘chevron dune’ part of the story. Pinter and Ishman have essentially the same main issue that I have blogged about: landforms that are morphologically identical to the so-called chevron dunes are well-known in the literature and they are called parabolic dunes. There is no need to introduce a new term:

We suggest that these Holocene features are clearly eolian, and that the term “chevron” should be purged from the impact-related literature.

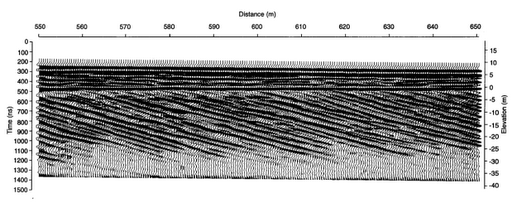

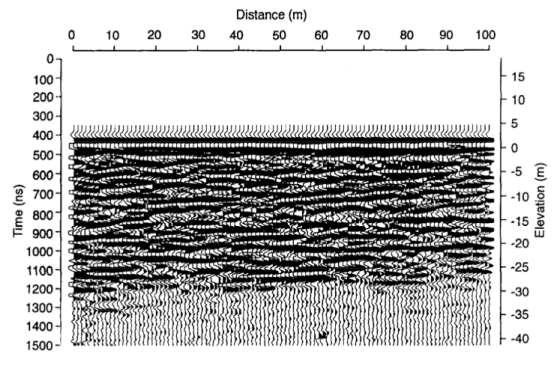

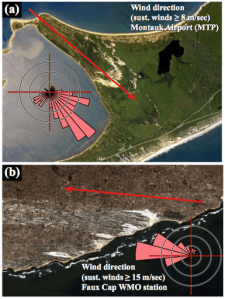

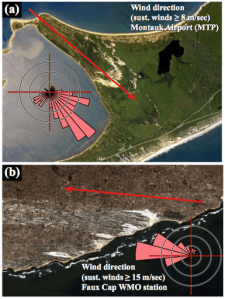

The eolian origin of the alleged megatsunami deposits is difficult to deny taking into account that wind direction measurements at two sites perfectly match the orientation of the sand dunes (figure from Pinter and Ishman):

Dallas Abbott and her co-workers address Pinter and Ishman’s criticisms in a short reply. This is what they have to say about the chevron dunes:

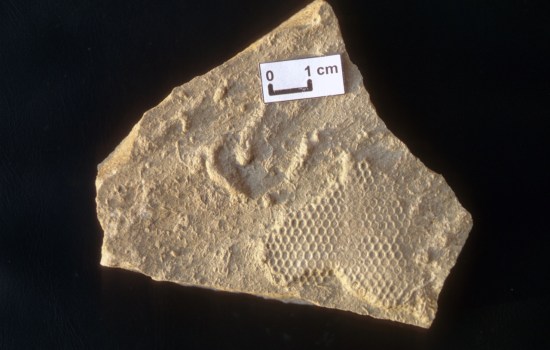

Pinter and Ishman also claim that chevron dunes in Madagascar and on Long Island are aeolian in origin. We visited both locations and found many features that seem incompatible with an aeolian origin. First, parts of the chevrons in both locations contain fist-sized rocks. These rocks are too large to be transported by the wind. Second, the orientations of the chevrons do not match the current prevailing wind direction. In both areas, some of the thicker sand deposits are being reworked into classic windblown dunes. The direction of movement of these dunes differs 8° to 22° from the long-axis of the chevrons. Third, the degree of roundness of the grains in the chevrons is not characteristic of wind transport over long distances. In both locations, sand grains on the distal ends of the chevrons are not well sorted or well rounded. Sand moved by the wind obtains an aeolian size and sorting distribution after only 10–12 km of saltation transport (Sharp, 1966); however, at Ampalaza in Madagascar, the chevron is >40 km long and rises to 63 m above sea level. At its distal end, the chevron is 7.2 km in a direct line from the coast and contains unbroken, unabraded marine microfossils and conchoidally fractured sand grains. It is impossible to transport unabraded marine microfossils to this location via wind-generated saltation. The site is too far above sea level for storm waves, and there is no local agricultural activity. The chevron was deposited by a tsunami.

Well, these seem valid counterarguments at first sight — but it would be nice and it would be time to see actual data: images, measurements, grain size distributions. Which parts of the chevrons are reworked into eolian dunes? What is the difference in the morphology of tsunami dunes and eolian dunes? How does this relate to flow dynamics? What are those “rocks” that occur within the dunes? Where do they occur exactly? And so on. The fact that the authors end their reply with an unqualified strong statement like “The chevron was deposited by a tsunami” suggests that they are unwilling to admit that not every piece of evidence favors their interpretation and that some legitimate questions can be raised. They do this after first admitting that parts of the dunes were indeed reworked into classic wind-blown dunes.

So, at least as far as the ‘chevron dunes’ are concerned, I have to concur with Pinter and Ishman’s harsh conclusion:

Both the 12.9-ka impact and the Holocene mega-tsunami appear to be spectacular explanations on long fishing expeditions for shreds of support. Both stories have played out primarily in the popular press, highlighting how successful impact events can be in attracting attention. The desire for such attention is understandable in an environment where science and scientific funding are increasingly competitive. The National Science Foundation now emphasizes “transformative” research, and few events are as transformative as an impact. In an era when evolution, geologic deep time, and global warming are under assault, this type of “science by press release” and spectacular stories to explain unspectacular evidence consume the finite commodity of scientific credibility.

References

Pinter, N., Ishman, S.E. (2008). Impacts, mega-tsunami, and other extraordinary claims. GSA Today, 18(1), 37. DOI: 10.1130/GSAT01801GW.1

Abbott, D.H., Bryant, E.F., Gusiakov, V., Masse, W., Breger, D. (2008). Impacts, mega-tsunami, and other extraordinary claims: COMMENT. GSA Today, 18(6), e12.

Firestone, R.B., West, A., Kennett, J.P., Becker, L., Bunch, T.E., Revay, Z.S., Schultz, P.H., Belgya, T., Kennett, D.J., Erlandson, J.M., Dickenson, O.J., Goodyear, A.C., Harris, R.S., Howard, G.A., Kloosterman, J.B., Lechler, P., Mayewski, P.A., Montgomery, J., Poreda, R., Darrah, T., Hee, S.S., Smith, A.R., Stich, A., Topping, W., Wittke, J.H., Wolbach, W.S. (2007). Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(41), 16016-16021. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0706977104