Ripples, dunes, cross bedding and cross lamination have always been some of the sexiest subjects in sedimentary geology. They are certainly responsible (in part) for my choice of a certain walk of life that consists of studying dirt. You might say that everything has been already said about ripples and dunes, and you clearly get that feeling if you read some of J.R.L. Allen’s work on the subject (and that can be a lot of reading, by the way) or look at the fantastic multimedia material that David Rubin at the USGS put together. [Of course, there are numerous other authors who have written great papers on the subject, but it is not my purpose here to write a history of bedform sedimentology. Although that would be an interesting subject, if somebody had the time for it.]

However, little of this material gets into the standard sedimentology and stratigraphy textbooks. Maybe rightly so: after all, textbooks are not supposed to include all the details about any particular subject. And maybe there are higher-density issues out there, like whether we should call something a turbidite or a debrite. [Sorry, I could not refrain from typing that].

Take for example climbing ripples. They form when several trains of ripples are superimposed on each other and they seem to ‘climb’, by generating stratigraphic surfaces that are tilted in an upcurrent direction. [Note however that these surfaces are *not* topographic – or time – surfaces; more on that later]. Numerous textbooks and many papers mention climbing ripple cross lamination, but often the explanation is something like “they indicate high rates of deposition”, or “the steepness of the climb and stoss-side preservation are a function of the ratio between suspended-load and bedload”. The question is, what do we *exactly* mean by ‘high rates of deposition’? If we cannot put numbers on it, it is not that informative. Also, by ‘suspended load’, do we mean suspended load concentration? Or deposition from suspended load and bedload, respectively? Those statements are not necessarily wrong, but they do not do justice to the models that have been published many years ago, models that actually have some numbers and equations behind the “conclusion” section.

The key paper that I am talking about is “A quantitative model of climbing ripples and their cross-laminated deposit“, by J.R.L. Allen, published in 1970 in the journal Sedimentology.

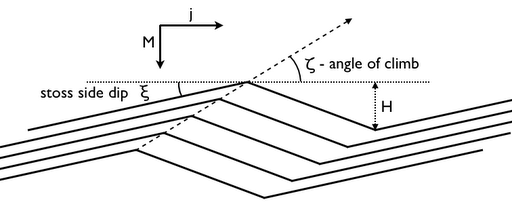

The most important relationship that Allen has derived links the angle of climb ζ (see the sketch below) to the rate of deposition M (measured in units of mass over unit time and area), the rate of bedload sediment transport j, and the ripple height H:

tanζ = MH / 2j

This is simply based on decomposing the sediment flux to and through the bed into vertical and horizontal components (plus a relationship between the horizontal sediment transport rate in ripples and the horizontal migration rate of the bedforms). Note that the quantity j refers to the sediment mass that moves through a cross section perpendicular to the general current direction, and does this by being part of the ripples themselves. In other words, there is no direct equivalence between M and suspended load deposition, and j and bedload deposition. Although it is possible that in general suspended load contributes more to M than deposition from bedload, it says nowhere that grains transported within the bedload cannot be deposited on the stoss side of the ripples and thus contribute to the vertical growth of the bed.

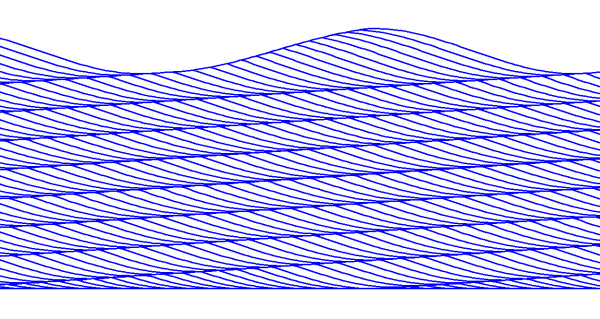

Obviously, if the angle of climb is smaller than the dip of the stoss side, there will be no stoss side preservation and the resulting cross lamination will look like in the sketch below (which, by the way, was quite an effort to generate in Matlab; you can easily do this and much-much more with David Rubin’s Matlab code, but I wanted to understand things a little better by coding something simple myself):

This is often called ‘A-type’ (or subcritical) climbing ripple cross lamination, but everybody knows what you are talking about if you “simply” call it climbing ripple cross lamination with no stoss-side preservation.

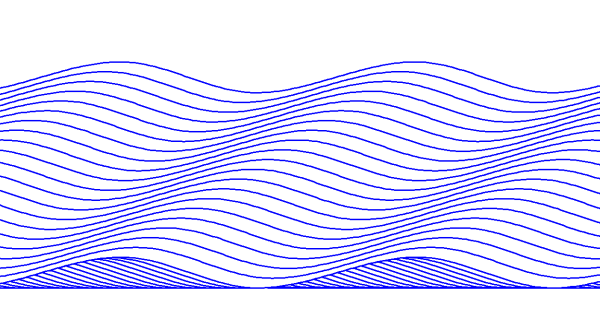

In contrast, aggradation is much more prominent if the angle of climb is larger than the slope of the stoss side, and in this case deposition takes place on the stoss sides as well, resulting in ‘S-type’ (or supercritical) lamination:

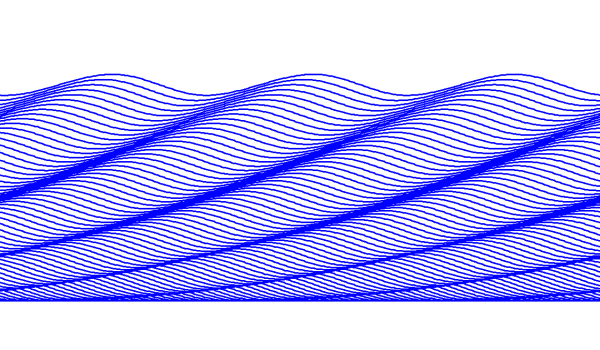

Of course, it says nowhere that the rate of deposition M or the bedload transport rate j must stay constant through time. If the ratio of these quantities changes, the angle of climb will change as well. This sketch shows an example where the rate of deposition M increases through time:

One of the main points of the paper is that there is a fundamental difference between the rate of deposition M and the bedload sediment transport rate j. A rate of deposition larger than zero means that the sediment transport rate within the flow must decrease from an upcurrent position to a downcurrent position; a simple mass balance tells us that this change in the sediment transport rate has to equal the rate of deposition. In other words, the rate of deposition M is a derivative of the sediment transport rate, and as such, does not belong in the same drawer of physical quantities as the bedload transport rate.

Along the same line of thought, Allen emphasizes that climbing ripple lamination says something about flow uniformity and steadiness. A uniform and steady flow can only form a single train of ripples; either non-uniformity or unsteadiness is needed to have climbing-ripple deposition.

That’s it for now; to be continued. It’s time to do my taxes.

Further reading: Brian has a Friday Field Photo and a Geopuzzle on climbing ripples. Here are some pictures and a movie of climbing ripples generated by a turbidity current in a flume.