A few months ago I commented on the fact that, despite numerous scientific and media reports, the existence of recent watery flows on Mars is far from being obvious or proven. While there are many rock formations exposed at the planet’s surface that clearly suggest flowing water some time in the ancient past – for example, the delta near Holden Crater -, many of the young gullies and debris fans have no unequivocal signatures of recent watery flows.

The high-resolution images with the relatively recent gullies were released in 2000, and a paper was published in Science about how these features suggest the presence of liquid water on the Martian surface. Last year, this idea seemed to get new support, in the form of some images taken in 2005 were showing sedimentary activity on crater walls, when compared to images shot a few years earlier.

(image from Malin Space Science Systems)

(image from Malin Space Science Systems)

The problem is, as I said, that nothing in these images suggest unequivocally the presence of water. Geologist Allan Treiman published a paper in 2003 stating this, but at that time his views were representing the minority viewpoint. Needless to say, the news reports got rid of the last remaining uncertainties and doubts in the story, and presented it as if it was 100% sure that liquid water exists today on Mars.

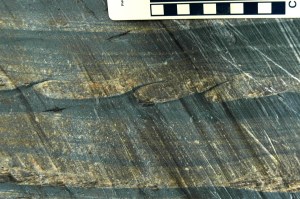

Now there is new evidence that the recent watery flows are not so watery after all. Rather, they are probably dust avalanches, dry flows similar to the ones that occur on windblown dunes here on Earth. Such flows can only form on steep slopes, that are close to the angle of repose. The problem, of course, is complicated – as many problems in science are – and there is no simple answer. For example, in the image shown above, you can see a fan that has been reincised after its deposition by its own feeding channel, so that the latest active deposition occurs further downdip. Such erosional valleys are probably associated with turbulent flow, suggesting that these fans were probably deposited by watery flows. More recent images (see below) also show details of erosional channels that are suggestive of watery flows. Unless the dust avalanches were highly turbulent density flows, similar to some snow avalanches, and they were even able to cut channels. Again, I think there is no easy and obvious answer.

photo from NASA’s Planetary Photojournal

photo from NASA’s Planetary Photojournal

In any case, there are two new papers in Science on this subject, check them out if you have online access (I don’t 😦 ).