I did some hiking recently in the Canadian Rockies. There is some stunning mountain scenery over there, with glaciers, lakes of out-of-this-world colors, icecap-covered humongous peaks, abundant wildlife, and so on. But some of the most exciting finds for a sedimentologist/geologist like myself must be the beautifully developed deltas that enter the glacial lakes. ‘Enter’ is actually an euphemism here, because the rivers are slowly, but surely filling with sediment these magnificent bodies of water, and it is only a matter of a few hundred or thousand years before most of the average size lakes become relatively uninteresting flatlands.

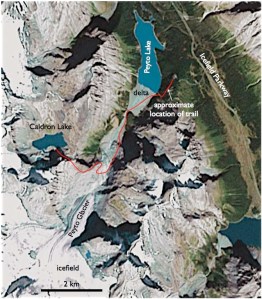

The delta at the updip end of the well-known (and somewhat overrated) Lake Louise is one of these lacustrine deltas. However, the one that really caught my attention is feeding into Peyto Lake. We got to the Peyto Lake overview area relatively early in the morning, when there was no wind, and the lake’s turquoise surface was perfectly smooth. Stunning view from high above, but most of my excitement evaporated (<– euphemism) when a busload of noisy (<– euphemism) tourists arrived and the viewing area suddenly felt like a Houston shopping mall on a weekend (<– exaggeration). So we started our descent toward the lake, on the trail that ultimately, if you are brave enough and rough enough (we were neither of these, but that is a different story), leads to Caldron Lake, above Peyto Glacier.

After only a couple of hundreds of meters, the population density dropped to zero, and my excitement not only went back to its previous levels, but exponentially grew as the lakehead delta started to take shape beyond the trees below us. You could see very well the active distributary channels sending slightly muddy or silty plumes into the lake. Because it was relatively cold, the glacier up in the valley was not melting too fast, and the discharge was small, so the plumes themselves seemed nice, but were barely noticeable.

This has changed during the day: as temperatures rose, the river that enters the lake became larger and larger, and by the time we got back to the lakehead delta in the afternoon, the plumes became much larger and much more evident.

The discharge of the river coming from the Peyto Glacier increases during the day and sends larger plumes into the lake in the afternoon

What is even more interesting is the fact that these plumes terminate relatively abruptly and it is very likely that they form density underflows in the lake. In other words, the sediment-rich water descends toward the lake bottom and flows down the slope as an underwater extension of the river, until it reaches the deepest parts of the lake. That is where it slows down and lets all of the sediment settle out, probably forming a graded layer, similar to the graded turbidites well known from marine sediments and rocks.

Such underflows often form in lakes when the sediment concentration in the river entering the lake is relatively high. In addition to the sediment concentration, the density excess can be enhanced by lower temperatures of the river. However, if the river is entering a sea or the ocean, it is much more difficult to form such underflows (that are often called hyperpycnal flows — just to make it a bit more confusing 🙂 ), because seawater has a lot of salt in it and therefore is denser than the river’s water. In this case, the sediment concentration of the river must be much higher to overcome the density of the seawater.

River, minibasin, delta, lake

As you walk up from the lakeshore toward the apex of the delta (which, by the way, has a classic triangular textbook delta shape), the size of the clasts on the delta’s surface slowly increases (statistically speaking). Further up, the valley gets narrow and then widens up again, giving place to a small minibasin. This minibasin probably was a lake some time ago, a lake that was completely filled.

The river is a Serious River

Where the delta meets the lake, you can easily get close to the distributary channels and their termination points. The coarser sediment tends to be deposited here from the flow, because the flow expands as it enters the lake and its velocity drops. Lower velocity means (1) lower shear stress at the bottom, and therefore fewer grains carried along the bottom, and (2) lower turbulence in the water column, which translates to less sediment carried in suspension. The enhanced deposition right in front of the channel mouth gives rise to a so-called distributary mouth bar, that tends to split the flow into two branches. With time, the mouth bar becomes an island, and the channel splits into two lower-order and simultaneously active distributary channels.

One of the distributary channels, with a nice mouth bar that splits the flow into two

It turns out, of course, that I am not the first to note how superb this little sedimentary system is — there are a number of studies that looked at the density underflows of Peyto Lake. This article tells us that Peyto Lake has a 7 m high sill in the middle, which splits the lake into two subbasins. Underflows (or turbidity currents) fill with sediment-rich water the updip subbasin to the spillpoint, and then the underflow spills over into the other subbasin. As far as I know, this is the only documented example of a truly ponded turbidity current. It has also been calculated that 61% of the sediment deposited in the lake comes from the underflows (most of the rest of the deposition is due to delta progradation).

Detailed view of the sediment-rich distributary mouths and their plumes

The sad news is that, with sedimentation rates similar to those observed today, Peyto Lake will be completely filled within less than 600 years. You should go and witness this jawdropping place before that happens.

* * *

PS: As Brian points out, the Peyto delta is remarkably similar to some of the experimental deltas generated at St. Anthony Falls Laboratory. See for example the image above — it is *not* a lake in the Canadian Rockies!